How to Start a Painting

Welcome to the beginning of a series I am putting together to show my process of creating an image. Hopefully it will be informative and helpful for my fellows in the pursuit of artistic greatness.

Step One: Familiarization

Before you begin any project, you must do the research to know what you're dealing with. First, find out who will be looking at the piece; children, young men, and elderly women all expect to see something different, and have different tastes. Second, find out about your subject. If it is a living thing based in reality, learn about its behavior, its habitat, etc. If it is something unliving, learn about its history and the culture that surrounds it. If your subject is something that doesn't exist, find out about the closest things that do.

For this project, I will be illustrating for a personal project, a card game I am working on. It is similar to Magic: the Gathering, in genre and demographic.

The card I will be illustrating is called Hippo Rider, the concept being some kind of humanoid warrior creature(s) that use hippopotamuses as mounts.

As I am already comfortable drawing the figure, my first step is to learn about the hippo. I go to wikipedia, watch nature documentaries, go to the zoo, whatever I can get my eyes and ears on so I can get a sense of the character of the hippo. By doing this I learn that they are massively powerful, fast sprinting, usually docile but potentially very dangerous and aggressive, communal, amphibious creatures. This is also the best opportunity to gather visual reference of hippos in various poses to use later.

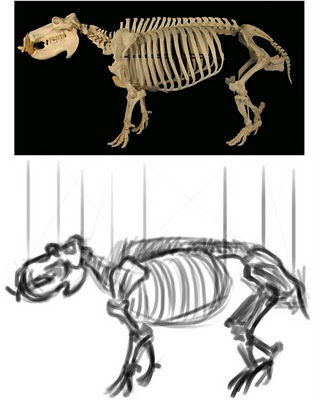

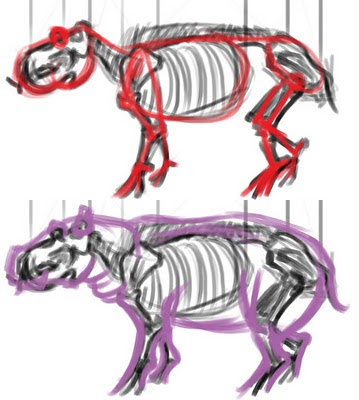

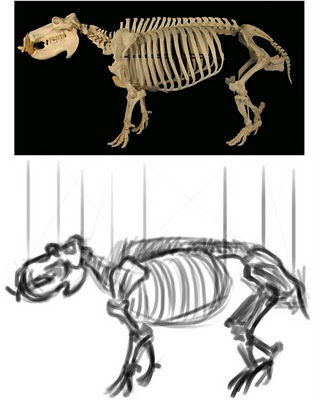

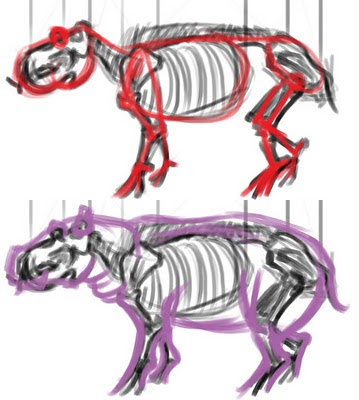

Now, finally, I can start drawing. I begin by learning the structure of the hippo by doing a couple quick skeletal overlay studies:

This gives me an understanding of how to arrange the hippo's anatomy, how it moves, and how its massive weight is held off the ground. It also gives me the opportunity to mentally catalog the unique visual characteristics of the hippo so I can draw it quicker and in such a way that it is easily identifiable in the image.

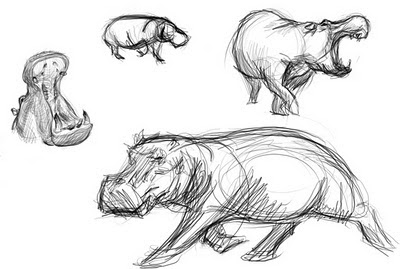

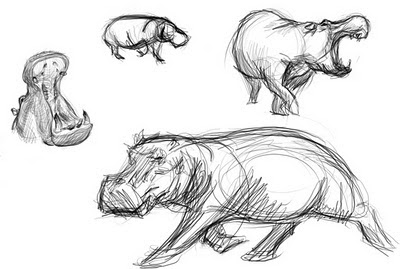

Then, I draw a few quick sketches from the visual reference I have collected, so my hand and eye get a feel for the kinds of curves and shapes that make up the creature. This also serves as a warm up for drawing the thumbnails. Warming up can be very helpful.

Step Two: Thumbnail Sketches

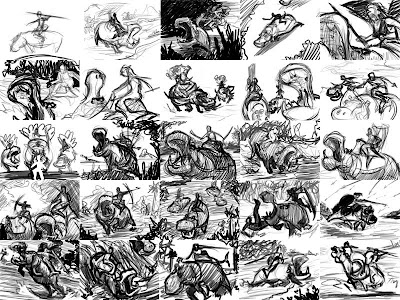

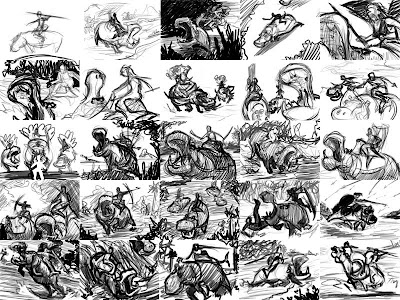

Next, I deal with composition. I work at the proportions of the finished piece, scaled down. I explore the various ways of displaying the hippo rider's form. At this stage, I don't have to put more than a few minutes into each thumb. Many artists put in less time, or do more thumbs, but I find twenty five gives me a lot of options, and allows each thumb to be clearer.

Try to think of each thumb as a visual experiment. Don't let any one thumb become too precious. Just put the idea down and move on. It can be easy to run out of ideas if you let yourself get too rigid. Only adhere to what is absolutely essential to the image, and let everything else change. In this case, so long as I show at least one hippo and someone sitting on it, it passes. Play with the angle that the subject is seen from, the situation the subject is in, etc.

In my next installment, I will talk about picking out the thumbs that work best, and moving into the rough sketch.